July 31, 2008

Behind the Music

July 30, 2008

July 28, 2008

July 25, 2008

July 23, 2008

July 22, 2008

A Dialogue on Public Responses to Inequality

How conservative are you?

Dave

I think income redistribution is (largely but not completely) wrong. I think the problems of sexism against women and racism against people who aren't white and Jewish are generally very overstated, or at least overstated by vocal political minorities who can overcome indifferent majorities, and government and institutional policies reflect this (family law, much affirmative action, contracting quotas, "wage gap" advocacy, etc.). I think legal color-blindness generally minimizes errors relative to color-consciousness. I think we have too much rather than too little economic protectionism and favoritism.

I do believe in principle that details matter (duh!), but many of my disagreements with median liberal opinion are stark enough that small differences in the specifics either of the policies or the world wouldn't make a difference.

Me

I have similar instincts, but I'm not confident enough in my knowledge of even the big picture (e.g., how bad these -isms are) to take a general stand.

What do you think we should we do about kids who are born poor and culturally disadvantaged?

Dave

I think I find "equality of opportunity" appealing. I think the battle for good public education is worth fighting. I especially like the class of arguments for good public schooling that emphasize the divergent interests of parent and child; I think these form a strong libertarian case for public schooling (I don't know if anyone has bothered to put it that way).

That's only a partial answer, though, because (arguably) it's possible for kids to be irredeemably fucked by their home lives (etc.), or for public schooling to fail them by being really shitty. I think I'm for state support for the very worst off, but the more provocative question is whether (and if not why not?) this same logic operates over the whole spectrum of different starting positions. As between myself and Dave^1, an otherwise-identical version of myself whose parents owned only 10% as many books, are differences in outcomes unfair? Should they be remedied by the state? It does seem unfair. But I think it's hard to systematically disentangle differences that are unfair from those that are fair.

The question of which differences in starting position are unequal opportunities is at least somewhat tricky. What about Dave^2, an otherwise-identical version of myself who's (even) lazier(!) than I am? I don't think Dave^2 deserves the same outcomes as I do, though this conclusion doesn't feel like it has a utilitarian logic (one could be devised; I'm not sure how I feel about this). And Dave^3, an otherwise-identical version of myself who's significantly dumber than I am -- are differences between his outcomes and mine unjust, at least insofar as he'd prefer to be closer to my outcomes? Some would say yes, some would say no, I think. I would summarize differences like those between Dave^2 and myself as differences in character (that does sound conservative!). I guess my anti-redistribution position grows largely out of the feeling that differences in outcome that correspond to differences in character are fair, and that those differences account for a large share of observed differences in outcome.

PS notwithstanding all the grappling above, I think it's easy to reach the conclusion that even the massively underprivileged should not be admitted to Amherst College, unless they demonstrate levels of proficiency similar to those required for the median student. The median student ain't even that bright.

PPS (Why the median student? I sorta figured the bottom of the class is crowded with special cases right now, and so not exemplary of good admissions standards.)

Me

I'm also committed to equality of opportunity; I suspect (hope) that the vast majority of people are and that disagreements are really about what meat to put on the concept's bones. The issue isn't ensuring equality but rather how much inequality is optimal (it's okay if only some kids get violin lessons).

I wish there were a good way of publicly addressing bad home lives/bad socialization. It seems that good public education and maybe a national propaganda campaign (to put it cynically) are the best we could do.

My off-the-cuff answer to your "more provocative question" is that we simply have to make a value judgment about where to make the trade-off between equity and efficiency -- hence common arguments in favor of a "right" to (a certain amount of, but no more) education, food, etc. It's also important to keep in mind that redistribution does not necessarily entail pie shrinkage; it provides social benefits such as crime control and the productivity of disadvantaged achievers who would otherwise have failed (especially if public funds are skewed towards promoting particularly productive achievement such as engineering degrees). Of course, there are borderline cases, but Dave^1 clearly has enough opportunity such that publicly providing for him would not be in the optimal basket of public expenditure; we'd be eating the harms of socialism at that point. It's also true that some people who don't have enough opportunity have character defects that render publicly lifting them up unproductive ex post, but that's a price that we've got to pay.

Given inadequate public assistance for the disadvantaged, institutions face the problem of identifying who would succeed if given the opportunity, and whether providing the opportunity would be worth it. This is of course difficult and depends on a given institution's values/purpose. This would be easier and largely obviated if there were effective public assistance from day one.

What about the simple fact that Dave^2 hasn't demonstrated as much proficiency as you but could have (so what if it would have been really hard -- see my discussion with Tarun on moral culpability)? His worse outcome encourages people to work hard and follows from allowing institutions to select for proficiency -- seems like good utilitarian logic. I don't get the point of Dave^3. Okay, he lost the genetic lottery. But his outcome is fair if he had enough of a chance to be all that he could be.

As for Amherst, I think underprivileged students should be given a bit of a leg up, especially if there are factors that suggest that they would readily thrive in a land of opportunity (obvious example: someone who did worse in high school just because she had to work two jobs, assuming this cause can be isolated). (Perhaps your [academically] median student point sufficiently accounts for this, since the median is lowered by athletic admitees and the like.) But I agree that Amherst is not the place for significantly unprepared applicants, no matter how unfair their unpreparedness. It's bad for the range of academic ability among students at an elite educational institution to be too big.

Dave

I don't think you're engaging the Dumb Dave^3 hypo. Your "okay, he lost the genetic lottery" assumes the conclusion at "okay." Why is it fair for someone to suffer worse outcomes for losing the genetic lottery? (Especially if it's not fair for someone to suffer worse outcomes for losing the social lottery?) Is this true for any case of losing the genetic lottery? You offer a utilitarian rationalization for this in the Dave^2 hypo (even if laziness is not necessarily genetic), but it's a justification that's specific to laziness / work ethic and doesn't cover the gamut of genetic lottery outcomes.

I think your response to the Lazy Dave^2 hypo suffers from a similar infirmity.

If I may free-associate in the guise of summarizing, I think you're relying heavily on unexamined notions of "could have": It's fair for society to treat Lazy Dave^2 worse because he "could have" worked harder; what does that mean? This can probably be boiled down to a pure utilitarian point, but is that what you meant? I think if you look closely at these "could have" intuitions, you'll find yourself at the notion of "character" I outline above, and the rough conclusion that it's okay to allow differences in outcome when they are explained by differences in character.

Of course, I broadly agree with your actual social-policy suggestions.

Anyway, gotta run, more later.

PS Of course, as Kaplow & Shavell show in their tautological book, giving any concern to "fairness" that's not completely anchored in utilitarianism fails to maximize utility. That compels one of just a few ways of resolving the interplay between fairness and utility here; I'm not sure which I choose.

PPS another class of redistribution I think I disapprove: Devoted Dave^4 graduates law school and decides to do "public interest" working, earning total pre-tax income of well under what Dave will make (inshallah); Devoted Dave^4 is subsidized by the government at the expense of Dave.

Me

I think you're needlessly complicating things. I agree with your "rough conclusion;" it seems to follow from the concepts of personal responsibility and equality of opportunity. Let me try to clear up my position.

Genetics are a built-in constraint (as of now) on opportunity; social environment is not. Dave^3 shouldn't starve if he's too dumb to earn a living, but it's okay if his stupidity keeps his standard of living below yours. True, this is no more "fair" than socially-induced inequality, but that doesn't matter. What matters is that the latter kind of inequality can be remedied to some extent; we can give Dave^3 books, but we can't up his INT.

To put it differently, everyone should be guaranteed a basic quality of life, regardless of opportunity concerns. (We have to assume that people who seem capable of providing themselves with a basic quality of life but refuse to either can't, are irrational, or both, not to mention the externalities they create.) This ensures that the losers of life's lotteries don't lose too badly (fairness rationale, though not necessarily pie-shrinking). Then we should consider public assistance to create equality of opportunity (equity rationale, no conceptual conflict with efficiency). Social lottery losers (such as the poor) are obviously a better target than genetic lottery losers (such as the dumb) because we can help them reach their potential; we can actually redress their inequality and possibly get a good return on our investment.

Regarding Dave^4, I presume you're okay with the "subsidization" resulting from progressive taxation. That said, I share your anti-subsidy inclination, but I worry about market failures. By the way, do you think donations to non-profit organizations should be tax deductible? (What if we could perfectly and costlessly identify which organizations serve the "public interest?") Might this policy promote efficiency by avoiding the transactions costs of government redistribution? (Or did I stop making sense?)

To be continued in the comments...

July 21, 2008

Fair and Balanced Nintendo Coverage

July 20, 2008

July 18, 2008

July 16, 2008

To Be Clear

I'm throwing rocks tonight.

July 15, 2008

Batman Insane

"In the new Batman film, “The Dark Knight,” many things go boom. Cars explode, jails and hospitals are blown up, bombs are put in people’s mouths and sewn into their stomachs. There’s a chase scene in which cars pile up and climb over other cars, and a truck gets lassoed by Batman (his one neat trick) and tumbles through the air like a diver doing a back flip. Men crash through windows of glass-walled office buildings, and there are many fights that employ the devastating martial-arts system known as the Keysi Fighting Method. Christian Bale, who plays Bruce Wayne (and Batman), spent months training under the masters of the ferocious and delicate K.F.M. Unfortunately, I can’t tell you a thing about it, because the combat is photographed close up, in semidarkness, and cut at the speed of a fifteen-second commercial. Instead of enjoying the formalized beauty of a fighting discipline, we see a lot of flailing movement and bodies hitting the floor like grain sacks. All this ruckus is accompanied by pounding thuds on the soundtrack, with two veteran Hollywood composers (Hans Zimmer and James Newton Howard) providing additional bass-heavy stomps in every scene, even when nothing is going on. At times, the movie sounds like two excited mattresses making love in an echo chamber. In brief, Warner Bros. has continued to drain the poetry, fantasy, and comedy out of Tim Burton’s original conception for “Batman” (1989), completing the job of coarsening the material into hyperviolent summer action spectacle."

July 14, 2008

July 13, 2008

July 12, 2008

Review - Encounters at the End of the World

I am a big fan of Herr Zog. But while Encounters provided me with an overall positive experience, it is a flawed film. First, the good news. Hearing the inorganically musical underwater vocalizations of Weddell seals through the theater’s multichannel speaker system was alone worth the price of admission. One of the scientists studying the pinnipeds aptly describes their varied and otherworldly sounds as Pink Floydian. I am also pleased to have beheld extended footage of the magnificent world beneath the sea ice. It is a teeming environment whose surface we are only beginning to scratch, and I cannot blame Herzog for choosing choral background music that perhaps screams “awe” a bit too loudly; there is no danger of it cheapening the majesty of the frozen stalactites or the splendor of the sunlight dispersing through the ice-ceiling. Lastly, I’ll note the humor, usually intentional, that Herzog uncharacteristically displays. His Teutonic deadpan is not his only comedic asset; he has a keen sense of the ridiculous, and ample targets among the many dubious denizens of the Antarctic.

My complaints are essentially twofold. First, the movie is disjointed. It is a hodgepodge of Herzog’s encounters with various Antarctic researchers and residents; there is no apparent order or theme. This is a minor criticism, as most of the segments make for fine viewing on their own, but it would have been more satisfying if Herzog had presented a unifying thesis or two about the Light Continent (aside from the oft-repeated observation that it is populated by a fair number of "professional dreamers"). He should have at least arranged the segments in a clearly meaningful sequence. At its best, the film made no more of an impression on me than “that was beautiful,” “that was cool,” or “I didn’t know that.” Second, and more significantly, Herzog’s narration is at times irritating. As someone who has studied climate change, I share his frustration and pessimism. But there is no call for saddling the film’s final moments with apocalyptic platitudes (e.g., “the end of human life is assured”) and a casual reference to global warming. These sentiments are incongruous with the rest of the film, which does not substantially address environmentalism and whose most haunting scene is of a mad penguin that abandons its flock and runs inland towards distant mountains, to certain death, with a singular determination. Herzog’s doomsayings, in any event, are better communicated by the satellite images of rapidly melting polar ice that we observe on a climatologist’s computer screen. I know that Herzog is capable of more thoughtful reflections on the impersonal and uncontrollable power of nature; for example, from Grizzly Man: “[W]hat haunts me is that in all the faces of all the bears that Treadwell ever filmed, I discover no kinship, no understanding, no mercy. I see only the overwhelming indifference of nature. To me, there is no such thing as a secret world of the bears. And this blank stare speaks only of a half-bored interest in food. But for Timothy Treadwell, this bear was a friend, a savior.” In Encounters, Herzog superficially and self-indulgently overstates his case. I’m looking forward to his next film.

Rating: 7/10

UPDATE: upon reflection, increased my rating by 1.

July 9, 2008

July 8, 2008

A Dialogue on Moral Psychology

This hopefully ongoing conversation stems from my previous post about the Stanford Prison Experiment. Of course, I welcome other participants.

Tarun

There's a fairly interesting documentary on the experiment: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v

There are people who think situationist psychology should lead us to revise our notion of moral responsibility. I'd like to think the soldiers in Abu Ghraib did what they did because they were more racist and/or more callous than me, but attributing the difference in action (or in my case, imagined action, I guess) to a difference in character rather than a difference in context is a mistake. The best predictor of moral behavior is situation rather than character. We assume the Abu Ghraib behavior is aberrant without understanding that the context in which they are placed fundamentally distorts practical reasoning. We assume that soldiers in a war-zone or in the Stanford Prison Experiment are more or less moral agents like us (their moral cognitive faculties operate more or less like ours) and on that basis judge their behavior pathological and therefore blameworthy. But the presumption is wrong - our cognitive faculties are significantly impacted by situational factors. We have reason to think that in a prison-like setting the behavior of the SPE subjects or the Abu Ghraib jailers is, from a psychological perspective, normal moral functioning.

I have a feeling that if we accept situationist claims, these kinds of exculpations are not going be restricted to extreme situations like war-zones. After all, finding a dime in a phone booth is apparently sufficient to produce a significant difference in moral behavior. If such apparently insignificant contextual factors have a quantifiable effect on our moral cognition, then the argument from the last paragraph should lead us to a radical skepticism about our folk theories of moral motivation and consequently moral responsibility. But then we already knew folk psychology is bullshit, right? Especially folk moral psychology.

Me

It's left-coast relativism like this that's destroying America! Seriously, though, not everyone goes apeshit in evilgenic situations. The issue of course is what we can reasonably expect of people. I'll focus on Abu Ghraib because the prison experiment was distorted by roleplaying (for those of you who haven't seen the documentary, one of the guards styled himself after a particularly sadistic guard in Cool Hand Luke in order to see, according to him, how much verbal abuse people would put up with; I wouldn't rule out shits and giggles). The issue of reasonable expectations is complicated by personal differences. If it's systemically viable, perhaps we should account for factors such as education, temperament, and life experiences, as we do age, when setting moral baselines. Shouldn't someone familiar with Milgram, Zimbardo, and moral psychology ideally be held to a higher standard than someone without a college education (leaving aside any perverse incentives that may result)? "Normal moral functioning" depends significantly on non-situational factors. Given my (perception of my) psychology, I can't imagine that I should be excused for committing atrocities akin to those in Abu Ghraib. Most of the soldiers apparently didn't cross the line, and I doubt most of them exhibited superhuman willpower; they probably just weren't as racist and/or callous as the abusers. Naturally this raises the question of how responsible people are for being callous or racist, but we have to put our foot down somewhere; we can't limit moral blame to the Jeffrey Skillings of the world and regard other wrongdoers as, to some extent, sociopathic. Essentially the problem seems to come down to what fictional account of moral responsibility the law should embrace, given that we can't excuse everyone to the extent that his psychology makes it hard for him to follow the law. I recall that Gideon Rosen had some persuasive things to say about the limitations of real moral culpability. Maybe I'll read this more recent paper of his.

Perhaps this is the same kind of arrogance that any of the participants in these experiments would have exhibited. But I stand by it. Just don't testify at my war crimes trial.

BTW, what's the story with the phone booth example?

Tarun

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki

"In one experiment that was done, the moral character of a person was based on whether or not a person had found a dime in a public phone booth. The findings were that 87% of subjects who found a dime in a phone booth helped somebody in need, while only 4% of those who did not find a dime helped."

July 7, 2008

The Persistent Provocativeness of the Banality of Evil

"By the end of the first day, nothing much was happening. But on the second day, there was a prisoner rebellion. The guards came to me: 'What do we do?'

"'It’s your prison,' I said, warning them against physical violence. The guards then quickly moved to psychological punishment, though there was physical abuse, too.

"In the ensuing days, the guards became ever more sadistic, denying the prisoners food, water and sleep, shooting them with fire-extinguisher spray, throwing their blankets into dirt, stripping them naked and dragging rebels across the yard.

"How bad did it get? The guards ordered the prisoners to simulate sodomy. Why? Because the guards were bored. Boredom is a powerful motive for evil. I have no idea how much worse things might have gotten."

Shit. Zimbardo goes on to parallel the experiment's situational drivers of abuse to those behind the torture in Abu Ghraib. Undoubtedly there are basic (banal) parallels. But what strikes me is how rapidly and intensely the experimental abuse escalated, given the situation (an experiment) and the players (of 70 male respondents, the 24 deemed most psychologically stable). It's one thing for low-ranking soldiers to get carried away over the course of overseeing suspected enemy combatants in a foreign prison. The grunts were in an unpleasant environment doing an unpleasant job for who knows how long, and they were not exactly the most reasonable bunch; racism, religion, revenge, and the like were among their motivations. This is not to excuse the atrocities they committed, just to put them in perspective. The experimental participants were presumably very different people in a very different setting, and it's harder for me to wrap my mind around what they did. I guess that's what's so unsettling about these experiments: everyone thinks "but I'd never do that," and then they do (they would; I wouldn't). Or is there more to Zimbardo's story? I'm curious what the participants were like. I was initially under the impression that they were students, which naturally blew my mind even more.

UPDATE: the participants were indeed mostly college (or college-bound) students according to this short documentary.

July 6, 2008

July 5, 2008

July 4, 2008

July 3, 2008

"Our Evolutionary Comrades"

Incidentally:

"Underground" by Barack Obama

Under water grottos, caverns

Filled with apes

That eat figs.

Stepping on the figs

That the apes

Eat, they crunch.

The apes howl, bare

Their fangs, dance,

Tumble in the

Rushing water,

Musty, wet pelts

Glistening in the blue.

July 2, 2008

Who You Callin' Undignified?

From "The Stupidity of Dignity" by Steven Pinker:

[Leon] Kass has a problem not just with longevity and health but with the modern conception of freedom. There is a "mortal danger," he writes, in the notion "that a person has a right over his body, a right that allows him to do whatever he wants to do with it." He is troubled by cosmetic surgery, by gender reassignment, and by women who postpone motherhood or choose to remain single in their twenties. Sometimes his fixation on dignity takes him right off the deep end:

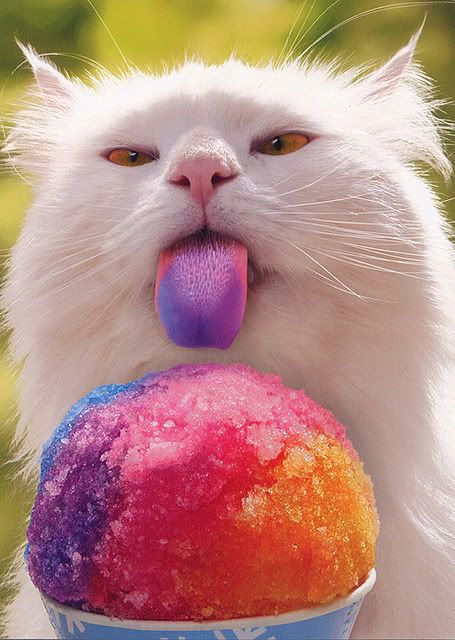

"Worst of all from this point of view are those more uncivilized forms of eating, like licking an ice cream cone--a catlike activity that has been made acceptable in informal America but that still offends those who know eating in public is offensive. ... Eating on the street--even when undertaken, say, because one is between appointments and has no other time to eat--displays [a] lack of self-control: It beckons enslavement to the belly. ... Lacking utensils for cutting and lifting to mouth, he will often be seen using his teeth for tearing off chewable portions, just like any animal. ... This doglike feeding, if one must engage in it, ought to be kept from public view, where, even if we feel no shame, others are compelled to witness our shameful behavior."

On you, maybe.